When Joost Bakker’s mother asked him to design a house for her, he said yes, with a proviso. Could he turn it into an internationally high-profile experiment in waste-free living before she moved in?

She might not have been too surprised – after all, her Dutch-born, Victoria-bred restaurateur, artist, designer and zero-waste activist son has a long track record in pushing the boundaries of the ways we live, eat and build. From the world’s first waste-free restaurant to art installations that highlight unsustainable lifestyles, Joost’s work is underpinned by a common-sense belief that we must think like nature and take personal responsibility for the future health of the planet and people.

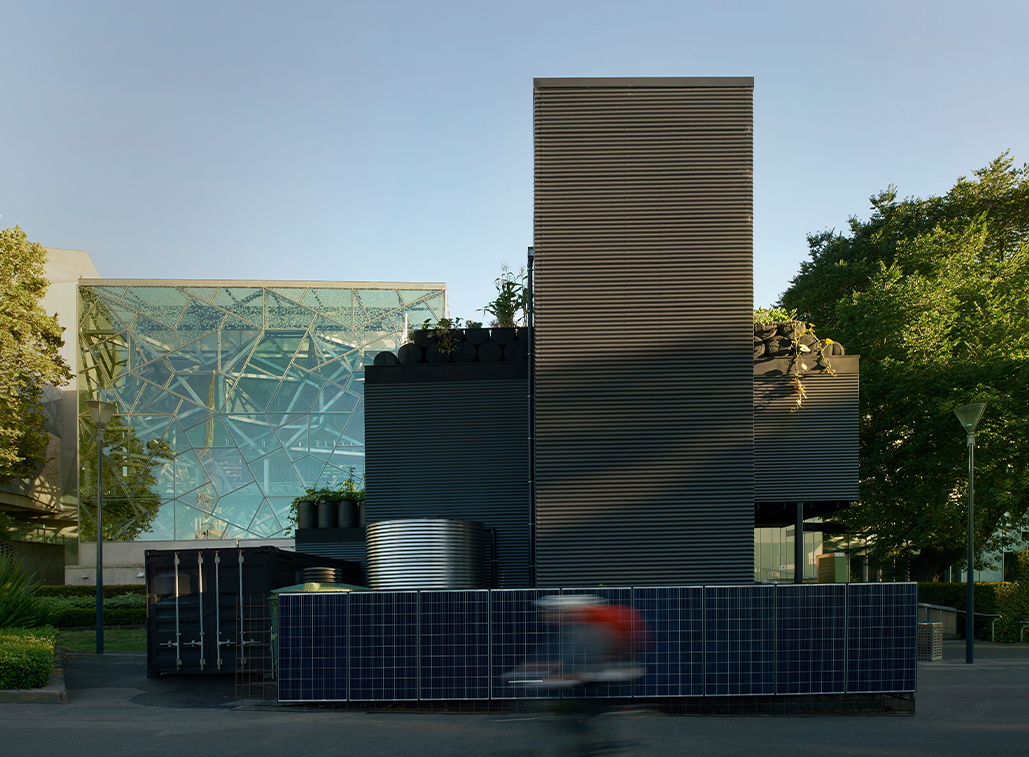

So, his mother’s house is, for now, the Future Food System, an entirely closed-loop building in Melbourne’s Federation Square complete with aquaponic systems, garden beds, beehives, grey water recycling, mushroom farms, mussel farm, styrofoam-eating beetles, pollution-busting soils and two resident chefs.

Now entering its second year, the house builds on Joost’s first instalment at Fed Square in 2008, when his Greenhouse restaurant saw potatoes growing in 120 tonnes of soil on the roof and staff wearing T-shirts declaring, “It’s all about the soil.” That slogan might have been ahead of its time, but, 13 years on, it has never rung truer for Joost, and after a decade of attempts, his most ambitious experiment yet fell into place last year when it instantly stirred locked-down imaginations.

“It’s almost like it’s meant to be. Because of the coronavirus, people were looking for new ideas,” he told One Hundred and One from his home in Monbulk, Victoria. “I’ve never had a project that has resonated as much as this one. People are craving connection, whether that’s urban gardening or looking after plants or fish or growing your own snails.”

Working around the pandemic, Joost hopes the house will burst with yet more diverse ecology when it reopens in summer 2021, showing the world that everyone, even those living in major city centres, can grow their own, eat more seasonally and cut waste.

“The biggest reason for deforestation and environmental degradation is our food,” he explains. “I’m a big believer that we don’t need anywhere as much land as we’re using, we just need to change the way we eat, what we eat, and we need to embrace and celebrate different foods.”

To that end, Future Food System will build upon the success of the yabbies produced last summer and will introduce more species of fish to the aquaponics pools. Joost will start growing snails and continue using mealworms and crickets to break down waste to support vegetables and herbs. The team grows 25 different kinds of mushrooms, matching them to the changing seasons, rather than having to cool or heat the environment. The plan is to take it, Joost says, to a whole new level.

That means more collaborators, including pioneering UK chef Douglas McMasters, former head chef of Joost’s Silo restaurant. “I get way too much credit for this stuff,” Joost says, “I just build the thing and it attracts brilliant people.”

As magnetic and smartly designed as the house is, he is adamant that its philosophy is something everyone can get behind. Whether sprouting chickpeas on a kitchen bench, or turning inner city tower blocks into scaffolds for tomato, strawberry and mushroom farms – recycling grey water and mulching used paper along the way – everywhere he looks, including car parks and basements, Joost sees potential urban food production. That’s because where humans live, they generate waste. And where there is waste, there is opportunity to sustain new life.

“Our cities could be and should be the most biodiverse places on earth. They could easily have a lot more diversity than even the most amazing rainforests,” he says. Ultimately, his dream is that urban food becomes the norm. One fan of his is a 70-year-old Northcote woman who has been producing 300kg of trout in her backyard for the past 15 years. Why shouldn’t every city home have a mini aquaponics system or a vertical garden? And why can’t we move away from eating near-extinct tuna and towards sustainable fish such as carp? It will no doubt take some major reframing before we see carp on supermarket aisles, but that doesn’t stop Joost from trying. Indeed, his ideas have always felt a few steps ahead of the mainstream, despite him labelling them “complete common sense.”

But does he feel like he’s going against the grain, given Australia’s abysmal record on climate change goals, say? “I think Australia is actually full of innovators,” he answers. “Revolutions are always driven by people – if we change our ways, politicians will always follow, they never lead.”

Next up is a book (made using waste-free production techniques) and in November Future Food System will re-open for tours, allowing the public a chance to observe the concept, systems and features first-hand. From April, he will dismantle the project and replant it in Monbulk, where his mother will finally move into her new home. Together, they’ll watch how the modest building develops to eventually support 1,000 species. He aims to make it the most biodiverse place on earth. Living closer to soil, with ecology built into our homes, is ultimately something we all have to strive for, because, to Joost, it’s part of who we are.

“We’ve spent millions of years evolving in an ecosystem and we’ve spent the last hundred years trying to remove ourselves from it. It just doesn’t work,” he says. “It’s a primal thing, it’s something we crave and it’s something we can’t live without.” In that case, let the revolution – and our cities – be green.

More than an iconic Melbourne landmark, 101 Collins Street is where influential businesses exchange exceptional ideas.